On the afternoon of 13 March 1878 at a charity concert at the Palazzo Odescalchi in Rome, Mary Wakefield started to sing. In the audience was Anne Crawford, the Baroness von Rabe, who was amazed by her performance. It had an Orphic, divine intensity:

There is something Bacchante-like in her singing. She seems to pour out her voice as though it were a generous wine. […] We were all quite wild about her. […] All the sober, steady-going English people clapped and stamped for an encore to her Buononcini song – and I felt, in the perfect peace of listening to perfect singing, as though my weary journey were quite repaid. Her voice is marvellous in its wonderfully even quality. The notes linger on the air like the tones of a finely-vibrating stringed instrument.[1]

Augusta Mary Wakefield (1853-1910) was no longer a mere twenty-four-year-old woman on a holiday tour of Italy with her family. She was now a ‘glorious […] exuberant creature’, a sort of goddess or priestess of flesh and blood, able to arouse the normally staid expatriate audience through her ‘crowning gift’ of music.[2] While this might seem to be exaggerated, Crawford’s claim certainly substantiates the view of Wakefield’s contemporary biographer Rosa Newmarch, that the singer was touched by ‘the light of genius’.[3]

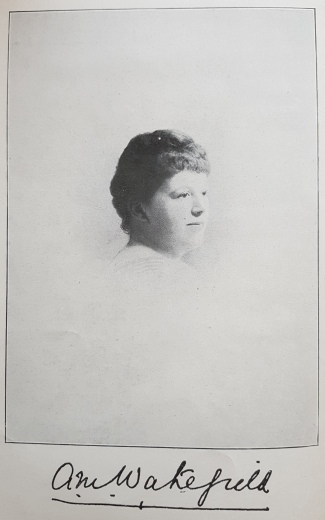

But this description of Wakefield, who appears both from Newmarch’s biography and from contemporary reports to have been a dynamic, energetic woman, contrasts greatly with the image presented in the photograph to the right. Here Wakefield is both a homely, but oddly-distant presence. The thick white cloud that she is hovering in, bodiless, sets her even further apart from us, as does her slight classical pose, in which she gazes across her shoulder to the distance, avoiding our eyes.

The photograph might well be a paradigm for the fate of many of the composers (particularly the women) who were adapting Swinburne’s lyrics for music in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Many of these composers are now ghosts, regardless of the extraordinary fame they commanded in their day. And despite the lack of celebrity aura in this photograph, Wakefield’s fame was indeed great, and not just because of her seductive voice. Two years after this concert in Rome, according to Newmarch, one of her songs, No Sir! (1880), became an extraordinary ‘hit’ which ‘carried her name practically all over the world in the course of a matter of months’.[4] Its follow up, Yes Sir!, appeared a year later, and was succeeded by dozens more songs, some of them collaborations with other popular composers of the day, including the eccentric Theophilus Marzials (1850-1920), who also adapted Swinburne’s poems to great acclaim, and whom she appears to have met while in Venice.[5] She also started a choral festival in Kendal (where the Wakefield family home, Sedgwick House, is situated) in 1885. This was part of Wakefield’s desire to encourage local, amateur music, she stated in an article for the Musical Times the year before, but what she actually had in mind was far more ambitious and radical. The festival, she hoped, would inspire a national movement, so that music would become ‘an integral part’ of the nation’s social life, for if ‘music as a serious art is ever to be appreciated and understood as it is in Germany, the formation of an educated, enlightened public is the first requisite’.[6] From its small beginnings in a tennis court at Sedgwick House, the festival grew year on year to host massed choirs, which would perform some of the greatest works in the choral repertoire, while she also encouraged the performance of the works of many contemporary composers such as Arthur Somervell (1863-1937), Jean Sibelius (1865-1957), and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912).

Her work inspired similar events on a national scale. An ‘Association of Musical Competition Festivals’ was formed, which, according to the Musical Standard, spread the ‘festival movement […] over the whole country’. On her death on 16 September 1910, the association raised funds for a Mary Wakefield medal to be awarded as a trophy for the following year, ‘or permanently’, at all ‘affiliated competition centres’.[7] As can be seen from my own copy, the medal bore the image of Wakefield from the above photograph, a picture of a lyre set into a frieze of roses, and the words of Martin Luther: ‘Music is a fair and glorious gift from God’.

Extraordinarily, her festival is still taking place, now as the annual Mary Wakefield Westmoreland Festival. But despite this legacy, Wakefield’s contribution to the life and growth of English music at the turn of the century has been largely forgotten. As Philip Bullock has noted in his work on Rosa Newmarch, Wakefield still does not even have an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.[8] Despite the publication of her music and its financial rewards, Wakefield – as a woman – was never quite able to shake off the adjective ‘amateur’ in descriptions of her work, and perhaps this past attitude still causes her work to be less visible than it should be.

But what of the Swinburne connection? Because of her friendship with Marzials, who knew Swinburne, she may have known the poet personally.[9] However, there is an interesting literary connection that is worth exploring, and not least because it proves the existence of the seductive charm that the Baroness von Rabe found in Wakefield’s voice. The writer Vernon Lee (1856-1935) was introduced to Wakefield by the novelist Mrs Humphry Ward at some time in 1882 after Wakefield’s popular music success had already begun. As Catherine Maxwell has shown, Lee wrote and dedicated her short ghost story ‘A Wicked Voice’ (1887) to Wakefield, after spending some of the summer of 1886 with her at the Palazzo Barbaro in Venice.[10] While Lee initially appears to have been reticent, even caustic about Wakefield, describing her in a letter to her mother as ‘fat’ and ‘grotesque’, she did warm to her greatly, perhaps to the point of romantic and sexual interest. In a later letter, she states that Wakefield was ‘a strange puzzle to me, but attractive with the attractiveness of extreme individuality’ and sang ‘like four & twenty seraphs’.[11] Lee would later be romantically involved with Kit Anstruther-Thomson, whom I have mentioned in relation to performances of Swinburne’s play Atalanta in Calydon.

Note the banner above the stage, which shows the same text as the reverse of the Mary Wakefield medal

The dedication to ‘A Wicked Voice’ reads: ‘To M. W. | In remembrance of the last song at Palazzo Barbaro, | Chi ha inteso, intenda [Whoever has understood, let him understand].’[12] The story concerns a Norwegian composer in Venice called Magnus (it is interesting to note that Wakefield was a friend of the Norwegian composer Edvard Greig, whom she met in Rome). Magnus is haunted by the ghost of an eighteenth-century baroque castrati, Zaffirino, whose appearance is heard rather than seen. The songs that this ‘wicked voice’ sings, prevent Magnus from writing his (Wagnerian) opera ‘Ogier the Dane’. He does, however, see a portrait of Zaffirino, and describes his face as

effeminate, fat […] with an odd smile, brazen and cruel. I have seen faces like this, if not in real life, at least in my boyish romantic dreams, when I read Swinburne and Baudelaire, the faces of wicked, vindictive women.[13]

The tempting, but dangerous voice is that of a woman in a male body, and perhaps a lyrical body that speaks of sensual pleasures and of life and death. It is a Swinburneian voice of wicked beauty that sounds rather like the Baroness von Rabe’s description of Wakefield’s singing at the Palazzo Odescalchi in Rome at the concert a few years earlier.

Wakefield’s adaptation of ‘Maytime in Midwinter’ (from Swinburne’s 1884 collection, A Midsummer Holiday and Other Poems) is dedicated to Marion Terry, the sister of the actress Ellen, although she was also an actress in her own right. Terry, Lee notes in various letters, was Wakefield’s constant companion, and, as Catherine Maxwell has suggested to me, it is possible that, as neither of them married, they were lovers. Wakefield’s dedication to Terry is set above the song title on the frontispiece of Maytime in Midwinter and so the whole song could be read as being directed at her. Underneath the song title is the first line of Swinburne’s lyrics: ‘The world, what is it to you, dear?’, which signals the theme of the song: the world is nothing when set beside the physical being of both the narrator and her subject. However wintry the year might become, the lyrics claim, Terry’s form and face create the radiance of a spring season: her smile turns the sky blue, her laugh makes the month turn into May. On the first page of the score, underneath the title, there stands an enigmatic quotation from Shelley’s ‘When passion’s trance is overpast’ (1824): ‘Which move | And form all others, life and love’.[14]

Despite the epigraph’s melancholic tone, Wakefield’s adaptation is bright and cheering, and turns rhapsodic early on, to stay firmly in this voice towards a rousing finale. I would imagine that like her earlier No Sir! (which sold more than 2,000 copies) Wakefield wrote the song with a music hall audience in mind. Rosa Newmarch is perhaps a little disparaging when she writes of Wakefield’s ‘temptation’ to follow up the success of No Sir!, with the implication that such a style of music was beneath her actual powers. And she warns that with so many successes so early on (which include such frivolous-sounding titles as ‘A Bunch of Cowslips’, ‘The Children are a Singing’, ‘The Love that Goes a-Courting, and the like), ‘Mary Wakefield now stood in danger of becoming the mere spoilt child of society’, but adds, ‘fortunately for music in England, [Mary] was not of the stuff that triflers are made of’.[15]

Wakefield has turned Swinburne’s words into her own. The original poem is ten stanzas long, but she has used only three to create a romantic song. Originally, however, Swinburne did not intend his words to mean or become anything romantic. While Maytime in Midwinter certainly uses romantic tropes (the twittering of birds, ‘mist and storms receding’, etc) the ‘child’ he talks of in the second stanza (illustrated left, but not included by Wakefield), is both an actual child and a metaphorical one – in that the spring, in May, is a child, being the earliest of the four seasons. It could also be an internal child, as the child-like thoughts of spring awaken the narrator’s heart and cast away cares. Swinburne wrote extensively about babies and children (and sometimes with ladles of syrup), but here, in this more sober poem, the midwinter visitation of a child lifts his seasonal melancholy so that grief seems like madness, all sunk ships are restored, and even the harsh call of the raven is turned into the note of a lark. This child laughs without care, searching through Swinburne’s bookshelves with wonder, and becomes ‘spring’s self’ standing at his knee. Swinburne’s subject is probably Bertie Mason, who, with his mother Miranda, came to live in the same house as Swinburne in 1879 as a five-year-old. Swinburne doted on Bertie and wrote many poems about or related to him, including a sequence of poems written during Bertie’s month-long absence from the house in 1881 called ‘A Dark Month’, which was published in Tristram of Lyonesse and Other Poems the following year.

The opening of ‘A Dark Month’. Its reference to ‘May’ in the first stanza links it to ‘Maytime in Midwinter’.

By taking out the child-like vision of Swinburne’s lyrics, has Wakefield also removed their potential innocence? Or is it that the lyrics are meant to retain their innocence even if their subject is different, so that a reader might not guess the truth, perhaps? Whatever the intention, Wakefield’s song is rather lovely. She obviously thought highly of the work and wanted to be associated with it, as the Royal Academy of Music’s archives has a copy of a Wakefield musical signature that refers to this piece. It contains both the opening bars of the melody and Swinburne’s lyrics.

Click here for the full text of Swinburne’s Maytime in Midwinter.

At the end of this month, I will be presenting at Vernon Lee 2019: An Anniversary Conference in Florence.

__________

[1] Rosa Newmarch, Mary Wakefield: A Memoir (Kendal: Atkinson and Pollitt, 1912), p. 36.

[2] The Baroness von Rabe was susceptible to the sensational, as the publication of her 1891 novella A Mystery of the Campagna suggests.

[3] Newmarch, Mary Wakefield, p. 9.

[4] Newmarch, Mary Wakefield, p. 42.

[5] Marzials dedicated his own song A Summer Shower (1881?) to Wakefield.

[6] Newmarch, Mary Wakefield, p. 79.

[7] ‘Memorial to Mary Wakefield’, Musical Standard, 4 February 1911, p. 68.

[8] Philip Ross Bullock, Rosa Newmarch and Russian Music in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century England (London and New York: Routledge, 2009), p. 78.

[9] For example, see The Swinburne Letters, ed. Cecil Y. Lang, 6 Vols (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959), II, 354.

[10] Catherine Maxwell, ‘Sappho, Mary Wakefield, and Vernon Lee’s “A Wicked Voice”’, Modern Language Review, Vol. 102, No. 4 (Oct. 2007), pp. 960-974.

[11] Maxwell, Modern Language Review, pp. 964, 966.

[12] Maxwell, Modern Language Review, p. 969.

[13] Vernon Lee, ‘A Wicked Voice’, in Hauntings and Other Fantastic Tales, ed. by Catherine Maxwell and Patricia Pulham(Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2006), pp. 154-81 (p. 162).

[14] ‘After the slumber of the year

The woodland violets reappear;

All things revive in field or grove,

And sky and sea, but two, which move

And form all others, life and love’.

[15] Newmarch, Mary Wakefield, pp. 43, 45.

Leave a comment